The poet Aaron Abeyta spoke these words in his keynote address at the 37th Annual Fishtrap Gathering of Writers near Wallowa Lake in eastern Oregon. This line, more than anything else, has stuck with me for almost a month. Writers are tasked with remembrance. Writers are responsible for carrying ancestral memory, childhood memory, cultural memory, everything that might be easily forgotten. Writing is a way of taking an experience, preserving it in a jar, and handing it to someone else, saying “Here, hold onto this while I’m gone.” Abeyta made it clear that in his view, remembrance is an act of love, as painful as it can often be.

I spent July recollecting the 1990s. I had the chance to see a defining ’90s creature-feature from my childhood, Tremors, in theaters. The hours I spent in a car driving from Indiana to Oregon to Arizona, I listened to podcasts, often movies and books and culture from the ’90s. Because of a last-minute schedule change, I spent a few days in western Washington after Fishtrap as an accidental tourist. I’ve driven past the turn to Roslyn a dozen times before, but never realized that it was the same Roslyn where Northern Exposure was filmed until eating cherry pie in North Bend, where Twin Peaks was filmed, and happened to overhear a customer behind me mention the other cult ’90s show filmed an hour away.

I can’t really claim proper nostalgia for the show. I watched Northern Exposure on DVD when I was in high school in the late aughts, more than a decade removed from the show’s original audience. The town of Roslyn remembers the show, though, and it was surreal to walk the same street that became familiar and mysterious to me on screen. I have a stronger emotional attachment to the fictional town of Cicily, Alaska, than other fictional towns. Northern Exposure luxuriated in the inexplicable, forcing its logic-driven protagonist to accept his limits, the meaninglessness and disorder of life, first for comic relief but later in the show with a more serious attention to the stakes of that mystery. It was the one artifact I remember from adolescence whose message was to confront impermanence rather than attack, deny, or confine it.

The truth is that lately, I’ve lost my appetite for TV. It was always on when I was a child, often when nobody was watching. It’s not that I find it bad or not worthwhile, but something about episodic structures turns me off these days. I’m reading more books, and watching more movies, and often thinking to myself at the end of a movie, that needed at least twenty more minutes. I want things to take time. I want to be slower.

The last night of Fishtrap, I talked with familiar writers from the Northwest. I met writers from Butte, Spokane, Moscow, Portland, Eugene. Every night, writers used their platform to discuss the importance of investing their time and energy into something larger than themselves, into a community that will outlast them and probably forget them.

Still half-asleep on that last night, I ran into another writer where I camped, who was packing her things for an early departure. She Bugs Bunnied a tarot deck from an impossibly small backpack pocket and asked if I was up for a reading. I drew the Three of Cups, the High Priestess, and the Princess of Pentacles. Her advice, after interpreting the cards, was to embrace feminine energies and be courageous in going through weird doors, to walk confidently into the unfamiliar.

Three days later, I found out a friend of mine had passed away two months earlier. Hers was the second funeral I should have gone to this year, but missed.

As easy as it is to talk about mining the past for stories, the phrase “writers are against forgetting” took on a very different meaning at the end of the month when I saw an image of Al Jazeera journalists mourning 27-year-old Ismail al-Ghoul, one of the most recent of the 165 journalists Israel has killed in Gaza since October. In the image, journalists hold up their PRESS signage, otherwise a symbol meant to protect war correspondents, writers, keepers of memory.

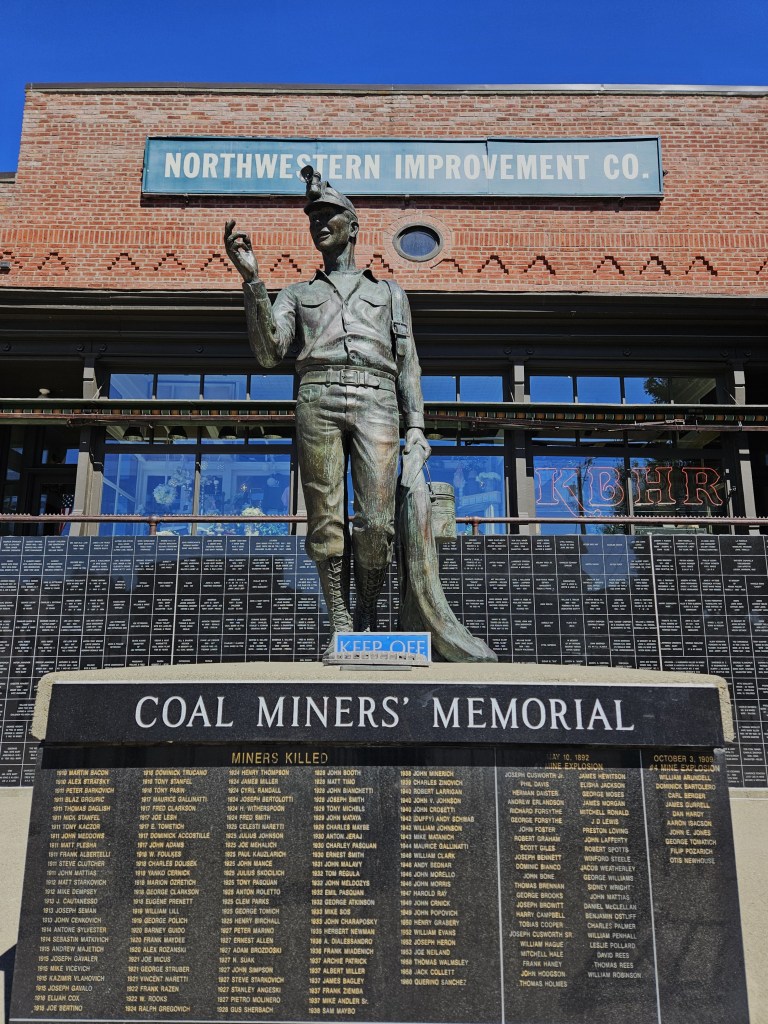

Roslyn, Washington, is also a coal town. There is an immense memorial to coal miners killed in the extraction process, overlooking the town’s main intersection. The names go on and on, and because the monument is located where tourists will stop to see the storefront used as the radio station in Northern Exposure, the town has proven that it, too, is against forgetting.

That’s a memoirist trick. There is a narrative thread on the surface and a hidden thread below. There is the town where a cult TV show was filmed, and then there’s a memorial to the town’s working class. Essayists remember everything all at once, all the time, because everything reminds us of everything else, because our job is to remember everything. This is an essay about traveling in July but it’s also about memory and TV and grief. It’s about writing, and writing about writing, and a willingness to disavow conclusion.

“I cannot hate them, the tourists, because I am one.” -Nabil Kashyap, The Obvious Earth

“I cannot hate them, the tourists, because I am one.” -Nabil Kashyap, The Obvious Earth

At the edge of the square, there is a sign telling visitors not to spread ashes of the deceased here because the scattering of human remains on this land goes against Navajo custom. I wonder how many tourists scattered their dead relatives at the Four Corners before the locals had to put up the sign. Despite the signs, tourists still come to the Four Corners and spread cremated relatives on this special dot on a map. I think about how weird it is to celebrate the alignment of state borders here in the Southwest. 150 years ago, this was Brigham Young’s Mormon territory called Deseret. 160 years ago, this was Mexico. 250 years ago, this was Spain. 450 years ago, this was Pueblo land. Statehood was only granted to Arizona in 1912. The land may appear static, but its cartographic meaning is always changing.

At the edge of the square, there is a sign telling visitors not to spread ashes of the deceased here because the scattering of human remains on this land goes against Navajo custom. I wonder how many tourists scattered their dead relatives at the Four Corners before the locals had to put up the sign. Despite the signs, tourists still come to the Four Corners and spread cremated relatives on this special dot on a map. I think about how weird it is to celebrate the alignment of state borders here in the Southwest. 150 years ago, this was Brigham Young’s Mormon territory called Deseret. 160 years ago, this was Mexico. 250 years ago, this was Spain. 450 years ago, this was Pueblo land. Statehood was only granted to Arizona in 1912. The land may appear static, but its cartographic meaning is always changing.

Every time I visit this city, it finds new ways to surprise me. There is no planning for contingency here. Last week, I returned to Albuquerque for the 40th annual Southwest Popular/American Culture Association Conference to present a paper (animal studies, rats, Paris, Ratatouille, and so on) alongside a broad, interdisciplinary spectrum of scholars.

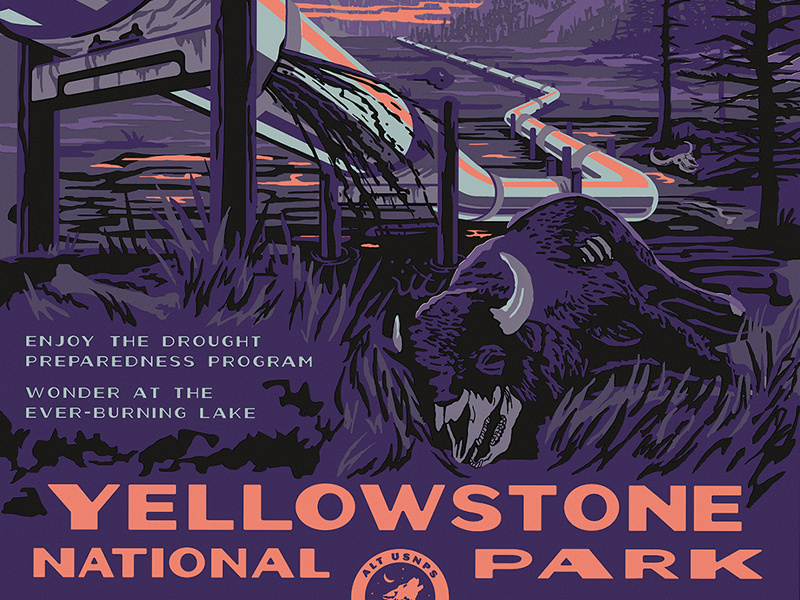

Every time I visit this city, it finds new ways to surprise me. There is no planning for contingency here. Last week, I returned to Albuquerque for the 40th annual Southwest Popular/American Culture Association Conference to present a paper (animal studies, rats, Paris, Ratatouille, and so on) alongside a broad, interdisciplinary spectrum of scholars. Popular culture studies finds a comfortable home in Albuquerque. This academic field, like the city itself, resists expectations. It forces people to recognize that grave concerns and lightheartedness can coincide.

Popular culture studies finds a comfortable home in Albuquerque. This academic field, like the city itself, resists expectations. It forces people to recognize that grave concerns and lightheartedness can coincide.

My plan for the break was to take a bus from Spokane to Missoula, and get a ride from there to Hamilton, Montana, to visit my grandparents, then travel to Arizona with my parents. To make a short story shorter, the bus was delayed, and now I’m stuck in Spokane for the night. I will depart in the morning, I hope.

My plan for the break was to take a bus from Spokane to Missoula, and get a ride from there to Hamilton, Montana, to visit my grandparents, then travel to Arizona with my parents. To make a short story shorter, the bus was delayed, and now I’m stuck in Spokane for the night. I will depart in the morning, I hope. There wasn’t much going on at the Spokane International Airport. Its two runways did not seem busy yesterday as I navigated the rigid airport security system. I diligently took off my shoes, placed my laptop in its own plastic tub, and placed my sparsely packed backpack in another tub. Shoeless, coatless, without my glasses and a little sleepy, I went through security. Past the body scan, I then waited as a TSA agent rummaged through my backpack.

There wasn’t much going on at the Spokane International Airport. Its two runways did not seem busy yesterday as I navigated the rigid airport security system. I diligently took off my shoes, placed my laptop in its own plastic tub, and placed my sparsely packed backpack in another tub. Shoeless, coatless, without my glasses and a little sleepy, I went through security. Past the body scan, I then waited as a TSA agent rummaged through my backpack.