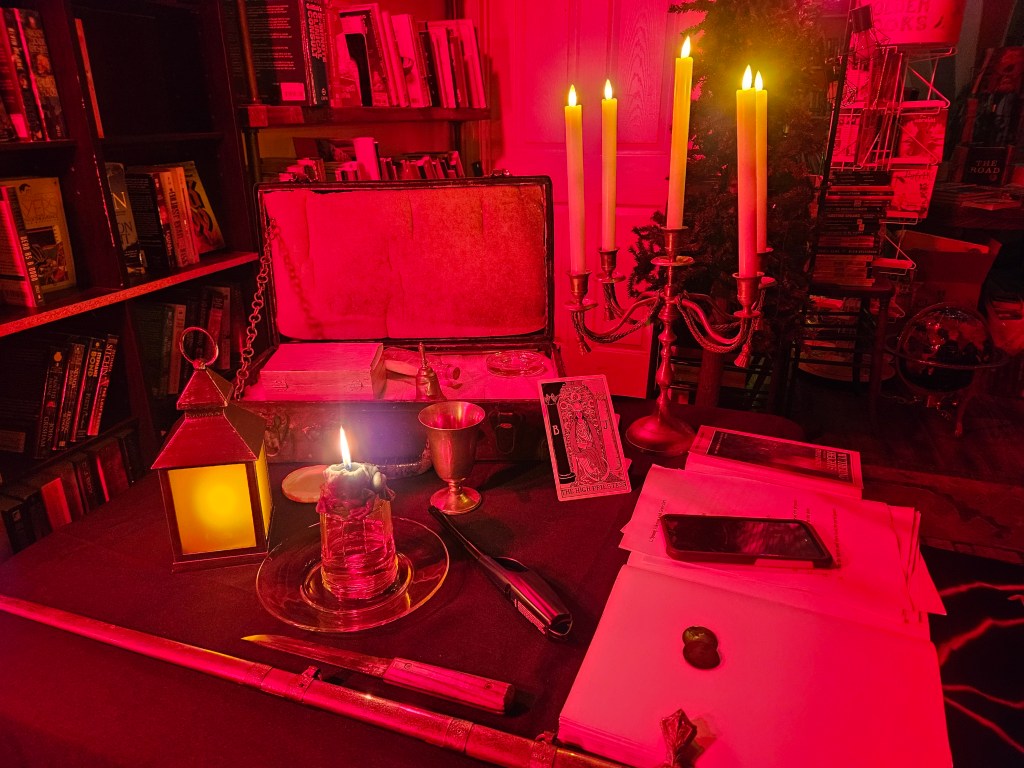

At 7:00 PM, the hooded medium taps his phone and the music on the Bluetooth speaker switches to some esoteric chanting. He unsheathes a sword and holds it over the participants—eight people consisting of one couple, one of the bookstore’s employees, his girlfriend, a trio of women who could be sisters, and myself. The medium says something muted as he taps the sword three times in the air, then repeats with a few sprinkles of water from a glass. He takes his role seriously, explaining that he is casting circles to protect the room from ill-intentioned spirits while still making room for benevolent ones.

He pulls back his hood to reveal a long white beard and thick glasses. He smiles and says in a Kentucky accent, “Hi, there, I’m Drew.” I want to add, “And you’re a Druid?” but I keep that to myself. I’m here to take this seriously. I write about horror movies and ghost stories for a living (or part of one). If nothing else, this is research.

We are gathered in an indie bookstore for a séance of the spirit of Emily Bronte, whom we will try to summon in southern Indiana using soil from the Bronte Sisters’ grave in England stored in a glass vial that looks like a test tube, a gift to the bookstore owner from a patron years ago. This is not a performance the way improv comedy is a performance, but I understand the guide’s showmanship. He asks us if there are any mediums in the room, anyone who is used to feeling strange, significant changes in temperature, casual premonitions, dreams that come true. A few participants raise their hands for each; I don’t raise my hand at all. As much as I want to believe, I am skeptical, always Agent Scully instead of Spooky Fox Mulder.

As an afterthought, the medium asks, “Are there any standup comedians here this evening?” I can’t tell if he’s looking at me while he explains that the impulse to crack a joke to fill an awkward silence breaks the tension necessary for a séance. This is a literary explanation: holding tension, like staying in pitch while singing, is a craft technique. Tension builds atmosphere, holds the reader’s attention, keeps us in the moment.

“As a child,” writes Melissa Febos at the end of Body Work, “I did not understand spiritual, cathartic, and aesthetic processes as discrete and I still don’t. It is through writing that I have come to know that for me they are inextricable” (153). A séance for a British author is aesthetically appealing during the month of October and cathartic to a certain extent, but I’m still hungry for spiritual meaning. I can appreciate the theatrics involved in any kind of ritual, a form of adornment like the robes a priest wears, the gold shimmer of a communion chalice. I know a campus pastor who often said, half-seriously, that a modern Eucharist should involve pizza and cola. A community meal would be spiritually satisfying and certainly cathartic, but the gravitas of gold and robes adds a layer of distinction, demarcating rituals from habits.

The medium passes around Emily’s grave soil. We hold it one at a time, seeing how it changes what we notice in the air, what magnetism we can find. It is heavier than I expected; the glass is cool to the touch, but not cold. One of the intuitive women in the room, though, feels its warmth. She walks around the room gauging the spirit’s rambunctiousness, looking for where the warmth is thickest, and stops in front of me. I don’t know where to shift my gaze; there is a density of warmth in front of me, she says. The medium’s glasses are so thick and the room is so dark that I think he is looking past me when he asks me if I’m comfortable proceeding.

Eager, almost giddy, he stands above me and draws a card from a tarot deck to see if the spirit of Emily Bronte or whomever else the circles invited in has a message for me.

He draws the Ten of Cups. He smiles. Red light reflects off his glasses, obscuring his eyes. He tells me that this is a sign that familial connections will come together soon, that questions of community and purpose will be resolved. That there is a reason to rejoice at something in the future.

I want to believe this. I’m actually taken aback by my own knee-jerk skepticism. I don’t know what spiritual force this is meant to resolve or why somebody would feel warm energy anywhere near somebody like me, so often told how cold I seem.

But this is just a prelude. The real séance requires two volunteers from the audience. One volunteer sticks his hand in a hole in the floor and leaves it dangling in the cold air above the basement. Another lies flat on his back with two death pennies on his eyes, pennies left on the eyes of the dead and uncovered decades later by gravediggers who had to shift bodies to narrower graves to make room for more of the dead. He has a vision of a worker whose whole family, generation upon generation, is at a mansion party, but the worker must leave. He almost hears the worker’s name, something with a T, but that’s all. The worker spirit must depart in a hurry, he cannot stay in our circle, in our waking world. Then, someone feels chills. Then, the warmth in the room falls away. The tension breaks before the ritual is over and the bookstore is a bookstore before it is supposed to be a bookstore. I walk out into the night, haunted by some ache I couldn’t name.